This low-cost yurt design combines basketry, wattle-and-daub, and basic lashing (similar to skin-on-frame boats). Not much more than a glorified tent, you can learn how to build a DIY yurt from sticks, string, and mud, making a very comfortable, durable, and beautiful tiny house, studio, or meditation space.

In 2007, I visited Bill Coperthwaite at his home in northern Maine and fell in love with the only round house I’ve ever been in that really works. The beauty of it grew directly from the circle itself; Bill didn’t try to make it fit a squared-off floorplan: no right angles, and the big spaces (the main living space is about 30 feet in diameter) were simply divided in half or in thirds. People in one portion had privacy but could reach any other part of the building easily via a generous circular “room” that was open all the way around the perimeter.

Bill’s designs would make a wonderful book (in addition to his classic, A Handmade Life), but I went home wondering how I could combine his ideas with my own favorite material: mud.

How to Build a DIY Yurt

Creating a Structure from Basket-Woven Willow

My first attempt was a hybrid stud frame building with wattle-and-daub infill. It worked! The mud provided all the necessary stiffening without additional lumber, and even on the wettest, coldest Pacific Northwest winter day, it’s comfortable and dry inside. The next year, I invited Bill out to lead a workshop. About 20 of us (many with no prior carpentry experience) built a beautiful 20-foot diameter, two-tier yurt with a living roof on the first tier, and shingles on the cupola. The bays in the framing of the bottom walls were filled with local willow woven by master basket-maker Margaret Mathewson, and backed with an earthen plaster.

Folks were delighted to learn the sophisticated carpentry required to cut all the compound angles with hand saws. Indeed, the framing was tighter than I’ve seen on many professional stick-built houses, Still, however, I dreamed of a design so simple that anyone could make it with minimal skills, no power tools, and no nearby lumber mill.

I went to the woods and cut an armful of hazel withies about thumb thick. These I lashed with baling twine into a rough, circular lattice, staked to the ground and contained at the top by a tension band made of bamboo and also bound with baling twine. The roof was reciprocal: all the rafters woven into a self-supporting cone, each stick supported by the previous stick, and supporting the next one.

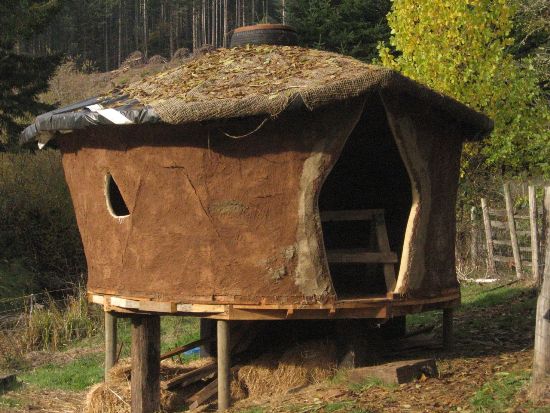

When I scaled up the design to 14-foot diameter, the same Margaret who had hosted Bill and the workshop let me thin out her grove of black basketry bamboo for the wall lattice. For the rafters, my neighbor let me cull some of the young Douglas fir saplings that had been shaded out in his forest.

When the lattice was up, we wove split-bamboo into it.

Adding a Natural Roof and Building Mud Walls

A bigger reciprocal roof was more challenging, but beautiful and functional (thanks to Tony Wrench for inspiration — his lovely cob and cordwood round house is another variation on the yurt). The ceiling was canvas drop cloth, and the roof membrane was a piece of heavy-duty vinyl billboard tarp, a waste product that it tough, waterproof, and flexible — perfect!

And when it was time to mud the walls, we invited friends and had a party. Windows (and the door) were easy to cut out of the lattice, and followed that pattern of diamond shapes. The final interior finish was a lime plaster.

Sharing Natural Building Techniques

I took the design down to Aprovecho Institute, in Cottage Grove, Oregon, to offer a week-long workshop as part of their 7-week Natural Building Intensive. In 4-1/2 days, 16 of us gathered and prepped all the materials, assembled the frame, raised the roof, and applied the first layer of mud. (The foundation/base had been completed beforehand.) In following years, we’ve slowed the pace to spend more time experimenting and addressing important design details around doors, windows, and the roof system. Several students have gone on to build their own yurts, and solved their own problems in new ways, with new materials as they find them. That’s appropriate technology!

Designed for the rainy Pacific Northwest, the generous overhanging eave protects the walls and keeps them from growing moss. The thick, insulative earthen walls keep even unheated interiors dry and comfortable. The only time I get to work on this is for a week in the summer, and every summer we have to start a new one! When you finish yours, send photos! And if you know of someone else building an innovative, low-tech yurt, please let us know so we can gather more material for our yurt-book project.

Kiko Denzer is a natural builder and skills instructor in Oregon. He’s rented a third-acre in the country for nearly 30 years where he grows a garden, bakes bread, builds and makes things (mostly using earth, or cob).Kiko wrote Build Your Own Earth Oven about how to transform the earth under foot into a wood-fired, masonry oven. Connect with him at HandPrintPress.com.

All MOTHER EARTH NEWS community bloggers have agreed to follow our Blogging Best Practices, and they are responsible for the accuracy of their posts. To learn more about the author of this post, click on the byline link at the top of the page.